By Molly Worthen

Contributing Opinion Writer

BEFORE the semester began earlier this fall, I went to check out the classroom where I would be teaching an introductory American history course. Like most classrooms at my university, this one featured lots of helpful gadgets: a computer console linked to an audiovisual system, a projector screen that deploys at the touch of a button and USB ports galore. But one thing was missing. The piece of technology that I really needed is centuries old: a simple wooden lectern to hold my lecture notes. I managed to obtain one, but it took a week of emails and phone calls.

Perhaps my request was unusual. Isn’t the old-fashioned lecture on the way out? A 2014 study showed that test scores in science and math courses improved after professors replaced lecture time with “active learning” methods like group work — prompting Eric Mazur, a Harvard physicist who has long campaigned against the lecture format, to declare that “it’s almost unethical to be lecturing.” Maryellen Weimer, a higher-education blogger, wrote: “If deep understanding is the objective, then the learner had best get out there and play the game.”

In many quarters, the active learning craze is only the latest development in a long tradition of complaining about boring professors, flavored with a dash of that other great American pastime, populist resentment of experts. But there is an ominous note in the most recent chorus of calls to replace the “sage on the stage” with student-led discussion. These criticisms intersect with a broader crisis of confidence in the humanities. They are an attempt to further assimilate history, philosophy, literature and their sister disciplines to the goals and methods of the hard sciences — fields whose stars are rising in the eyes of administrators, politicians and higher-education entrepreneurs.

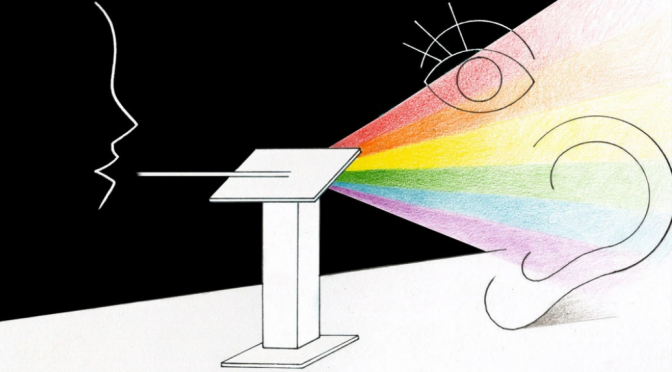

In the humanities, there are sound reasons for sticking with the traditional model of the large lecture course combined with small weekly discussion sections. Lectures are essential for teaching the humanities’ most basic skills: comprehension and reasoning, skills whose value extends beyond the classroom to the essential demands of working life and citizenship.

Image credit: Baptiste Alchourroun