By Molly Worthen

Contributing Opinion Writer

Chapel Hill, N.C. — The first debate between Hillary Clinton and Donald J. Trump featured plenty of magical thinking, but it was a nonreligious event. Neither candidate mentioned God. The second debate may be no different: Voters see Mr. Trump as either a prophet or an angel of death, but the only religion that interests him is his own faith in his “winning temperament.”

As to Mrs. Clinton: The news stories that have dogged her — the email server; Benghazi; the “basket of deplorables” quote — don’t have much to do with religion. She has been private about her Methodist faith, and no earnest Sunday school memories will sway voters who view her as fundamentally untrustworthy.

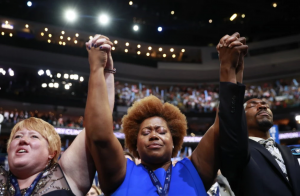

Yet religion helps explain why Mrs. Clinton has struggled to unite the Democratic base. I’m not talking about the faithful who look for the resurrection of Bernie Sanders, but a real left-wing religious revival. Its prayers, preaching and theological battles look very much like the revival that energized the civil rights movement a half-century ago. Today’s revival is divided against itself, as it was back then.

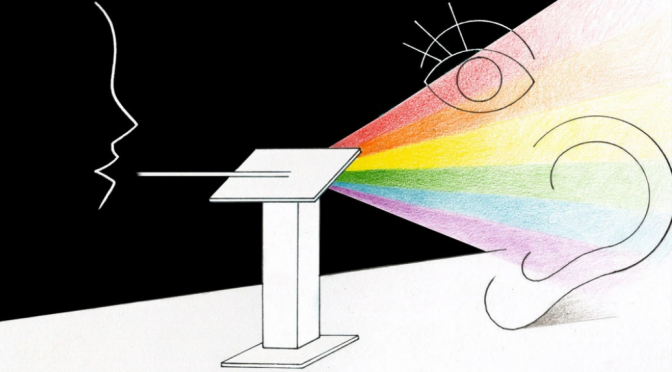

This revival’s more moderate leaders can’t corral the young radicals who want revolution and who reject not just the Democratic nominee, but the basic assumptions of modern politics. The clash goes deeper than policy or strategy. It is a theological rift: Is religion founded in submission to unchanging principles or is it a protean revolutionary force, a tool of self-empowerment?

Image credit: Damon Winter/NYT