Sitting through a 40-minute lecture is not, generally, a popular pastime in our distracted culture. But on a typical Sunday at The Summit Church in Raleigh, the room goes from worship-band jamming and raucous applause to rapt silence as J.D. Greear, 48, walks onstage.

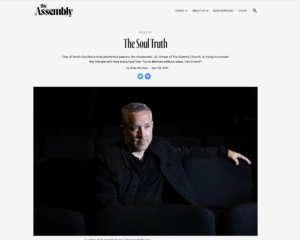

His salt-and-pepper crew cut, well-groomed stubble, black polo shirt, black zip-up jacket and khakis are the uniform of a pastor who is cool, but not too cool—who wants to bridge the formidable Boomer—Gen Z chasm.

All around the sprawling auditorium, people are flipping through their Bibles and getting ready to take notes. Occasionally a glowing screen lights up the dim room, but it’s just someone consulting a Bible app.

“Christian love—1 Corinthians 13—is countercultural, and it’s often straight-up confrontational,” Greear says.

Greear’s sermon is about confronting the self-centered motives that often lie behind pious behavior: “Apart from love, Paul says, every other religious act is empty, it is hollow, it is displeasing to God and it’s just annoying to other people … You tracking with this? Because, see, this is what the Corinthians were: They were religiously impressive on the outside, but full of selfish immaturity on the inside.”

He glances occasionally at the small black binder of notes in his left hand, his eyes otherwise locked on the cameraman back near the tech booth. Most people in the congregation are watching Greear on one of the room’s giant screens, as are congregants at Summit’s 10 other campuses around the Triangle.

Greear gestures with the amped-up energy of a professional who knows how to calibrate for the camera without seeming hammy in real life. He never admonishes the congregation for too long without a dimpled smile and some comic interlude of repentance for his own idolatries, whether it’s pride, people-pleasing, or his excessive love for Nicolas Cage movies.

The man can preach. It’s not hard to understand why so many congregants cite Greear’s sermons as a major reason they are here—over 8,600 on an average weekend (another 7,000 watch online). Summit’s Easter service at Raleigh’s Walnut Creek Amphitheater drew almost 16,000.

Still, the Triangle is a hard place to win souls for Jesus. It’s full of transient college students, well-educated skeptics, and immigrants from other religious backgrounds. Like everywhere else in the Western world, the Triangle has lots of exhausted and apathetic people who would prefer to sit alone on the couch on Sunday morning. Yet Summit is preposterously determined—more determined than most churches—to win people to Christ.

What’s even more unusual, in our polarized times, is this: Greear is not doubling down on us-versus-them, but trying to build bridges—both at Summit and during his recent term as president of the Southern Baptist Convention. Greear’s presidency was a testy three years spent trying to get the country’s 14 million Southern Baptists to wrestle more openly with racism and churches’ widespread failure to listen to victims of sexual assault.

Christian love, he said in his sermon on 1 Corinthians 13, “sometimes presses down to expose what you are hiding … love does not naively close its eyes when difficult questions are in order.”

Greear’s tightrope walk may be attempting the impossible: to pull back from the culture war without yielding to secular values, and to serve and love non-Christians—while still begging them to see that they are damned without Jesus.

Read more here.

Image credit: Maddy Gray