This is the season for final exams, but maybe we should drop the pencils, paper and keyboards and start talking instead.

The thought is scary at first. If Chidera Onyeoziri had known that her introductory sociology course required oral exams, “I’m not sure I would have taken the class,” she told me. She was a sophomore at Hamilton College in Clinton, N.Y.; she had never taken an oral exam before.

“I remember putting in a lot of work, spending a lot more time on the course than I otherwise would have,” she said. During the first exam of the semester, she coped with her nerves by getting out of her chair and pacing. Her professor, normally so friendly, stared impassively and interrupted her with questions.

Looking back on the class after a few years, “I can definitely say that’s the course that I remember the most of, and that may be a function of the oral exams,” said Ms. Onyeoziri, today a student at Harvard Law School. Now that she’s planning to be a lawyer, she added, “public speaking is something I really can’t do without, so the oral exams were probably, in the long run, more helpful to me than written exams.”

As finals loom for most college students across America, it’s worth revisiting oral exams. The phrase brings to mind stone-faced interrogation intended to expose a trembling student’s “skull full of mush,” in the words of Professor Kingsfield in “The Paper Chase.” But if done right, oral exams can be more humane than written assessments. They are a useful tool in grappling with many problems in higher education: the difficulties of teaching critical thinking; students’ struggles with anxiety; everyone’s Covid-era rustiness at screen-free interaction — even the problem of student self-censorship in class discussion.

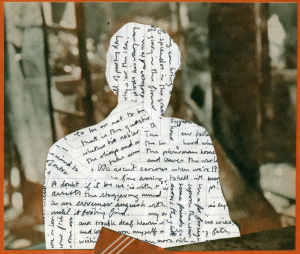

Image credit: Matt Chase