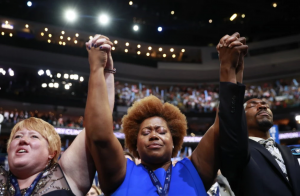

The only decor in the little, white-walled church is a black cross and a text mural in large, black, sans serif letters: “Jesus Loves You Beyond Belief.”

The renovation was barely finished in time for the first official Sunday service. Blue painter’s tape still lines open floor ducts, and the tang of newly refinished floors pricks the nose.

Pastor Brian Pell, 30, looks relieved. He’s been working to plant this new congregation for over a year and today is “the launch,” in church-planting lingo. Outside on this mild September morning, on a slightly overgrown dead-end street near downtown Carrboro, churchgoers file past a card table stacked with donuts—not a flood of people, but not a trickle either. By the time the worship band picks up their guitars, about 80 people have turned up.

The scripture for this Sunday is from the second chapter of Paul’s letter to the Colossians, displayed on television monitors flanking the stage. It’s a passage about how harsh rules on food, drink, and worship are not the point of the gospel. This suits Carrboro, a kombucha-drinking, Pride flag-festooned town of about 21,000 next to Chapel Hill. When a young woman stands to read the day’s text and starts talking about wives submitting to husbands, people trade confused glances. When she gets to “slaves, obey your human masters in everything,” she realizes her mistake: “Wait a minute, I’m reading Colossians 3! Can we just start the service over?”

The congregation bursts into friendly laughter. This is Vintage Church Chapel Hill/Carrboro’s first service, and the goof breaks the tension—a little wink from the Holy Spirit. The slip is also telling. While Christians might prefer to lead with the agreeable parts of the gospel, sooner or later they run into the awkward fact that Jesus and his disciples were not, ultimately, warm and fuzzy or an easy fit in the 21st century.

Pell knows this as well as anyone. He’d planned to preach straight through Colossians, and would have to confront Colossians 3 the very next week.

Carrboro may seem like an odd place to start an evangelical church, with its rainbow crosswalks, informational lectures on hemp at the local grocery co-op, the spoken-word poetry, “anti-oppression talks,” and craft tables at its monthly “Really, Really Free Market.”

But perhaps all this makes Carrboro an ideal mission field for Christians. In our multicultural, secular age, Pell may convince nonbelievers that the best answer to their postmodern problems is a 2,000-year-old faith.

Image credit: Maddy Gray