By Molly Worthen

Contributing Opinion Writer

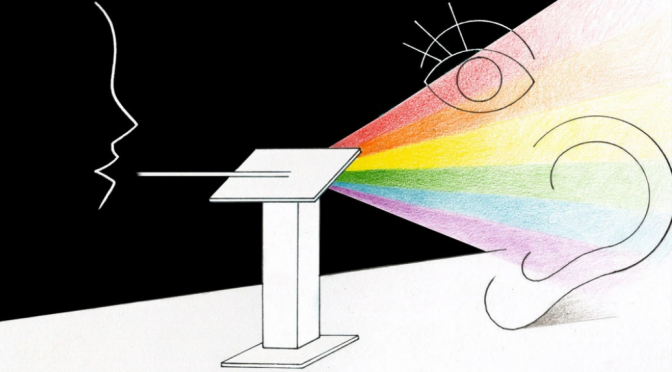

THE arrival of the “post-truth” political climate came as a shock to many Americans. But to the Christian writer Rachel Held Evans, charges of “fake news” are nothing new. “The deep distrust of the media, of scientific consensus — those were prevalent narratives growing up,” she told me.

Although Ms. Evans, 35, no longer calls herself an evangelical, she attended Bryan College, an evangelical school in Dayton, Tenn. She was taught to distrust information coming from the scientific or media elite because these sources did not hold a “biblical worldview.”

“It was presented as a cohesive worldview that you could maintain if you studied the Bible,” she told me. “Part of that was that climate change isn’t real, that evolution is a myth made up by scientists who hate God, and capitalism is God’s ideal for society.”

Conservative evangelicals are not the only ones who think that an authority trusted by the other side is probably lying. But they believe that their own authority — the inerrant Bible — is both supernatural and scientifically sound, and this conviction gives that natural human aversion to unwelcome facts a special power on the right. This religious tradition of fact denial long predates the rise of the culture wars, social media or President Trump, but it has provoked deep conflict among evangelicals themselves.

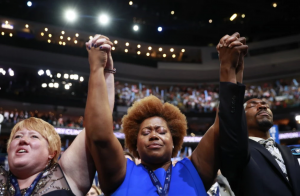

Image credit: Alex Webb/Magnum